The Temple of Apollo in Delphi

The entrance to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi contains the above inscription, ‘gnothi seauton’. This translates in English to ‘know thyself’, and is taken to be one of the fundamental areas of knowledge for anyone wishing to excel in life pursuits. It is also one of those things that are far easier to state than to accomplish.

The difficulty in knowing thyself comes partly in the wide variety of areas of knowing that are necessary. There are a myriad of those areas and each of those areas can be viewed from a number of perspectives. The main issue with knowing in this context is the sheer volume of things to know. However, an active sense of curiosity, a quantity of discipline and a quantity of time cover most of what is needed to overcome this challenge.

Where a real problem lies for all of us is in knowing the impact of the concept of ‘Us’ and ‘Other’ on our behaviour. In this piece, we will look at the impact that the Other has on the self. This does not imply that Us is somehow less impactful, just that the two are each complex enough in their own right to be dealt with separately.

Enter the Other

According to recent research done by Robert Sapolsky and outlined in his book, ‘Behave: The Biology of Humans at our Best and Worst’, our concept of the Other moulds and governs a significant portion of our perspectives and judgements which, in turn, modify and control our behaviour.

So, what is this Other that we need to know? It’s probably easiest to start this discussion with what the Other is not. The Other is not external. That is, the Other is an internal concept that is separate from external reality.

The Other is a tool that we use to sort friend from foe, safe from danger, good from bad, comfort from discomfort, happy from sad, and so on. The Other is a hard-coded neural feature that has evolutionary roots in the primordial ooze. The Other is about protection and survival. The Other is a barrier to performance.

To give you an idea of how the Other works, 50 milliseconds is all that is needed to make a judgement of Us or Other. Obviously, this is not enough time for this judgement to register as conscious thought. However, the judgement still registers in the brain in the Limbic System and related parts of the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). The Limbic system makes its assessment and gets to work notifying the appropriate associative areas of the PFC where a judgement is made. The judgement is then matched to a closest approximation of past experience. A secondary, unconscious decision is made, based on that experience, and a reactive behaviour is generated. Bingo, bango, bongo, you are now behaving in response to a non-conscious perception with no idea that the behaviour is even occurring. Functioning just about as quickly as a knee jerk reaction, this brain jerk reaction is a continuous process. This is what makes it so powerful. This is what makes it so difficult to know.

What is the Purpose of the Other?

From an evolutionary standpoint, it was essential to develop a mechanism to determine a danger and equally important to quickly conjure a strategy to manage the danger. The Other is the mechanism for identifying the danger and the non-conscious (fast) behaviour is the strategy. To make this process even more complex, the broader the range of behaviour of the organism, the more wide-ranging the mechanism/strategy needs to be.

Currently, our understanding of human neuro-physiology makes nearly everyone over the age of 12 familiar with the concept of fight or flight (and the additional F’s that get added). This is just one of hundreds of mechanism/behaviour combinations that are continuously active. Each combination is specifically designed to protect from or prevent injury or insult. How these mechanism/behaviour combinations developed is of critical importance to performance managers.

Why is this a Problem for Performance?

Our existence a mere 10,000 years ago was far more precarious than it is now. A range of 104 years is an instant in evolutionary terms. Our mechanism/behaviour combinations were ‘designed’ via evolutionary processes to manage an environment that was significantly different from the environment that we experience today. In addition, the cost of false positive reactions was far lower than it is today. The keenly honed sense of Other that was so essential to our ability to flourish in the past is now responsible for our propensity to over react to encounters that we identify as Other. We rain havoc down on our proximal environment without even being aware of what we are doing. And this can make performance suffer. These reactions are commonly referred to as the ‘Stress Response’. A detailed examination of this phenomenon can be found in Sapolsky’s book, ‘Why Zebras don’t get Ulcers‘.

For example, we evolved as social mammals. As social mammals, it was critical to be able to identify our social group (Us) from the Other. At the time that this evolution was taking place territories only rarely overlapped. Contact with Other groups was relatively infrequent although often highly violent until mutual exchange of value exceeded the risk of contact. In a relatively short period of time, far less than the time that it would take to evolve a refined mechanism for Other, we now find ourselves living scant meters from all manner of ethnically and culturally different groups. The naturally understandable but socially unacceptable prospect of racism is a direct result of an highly developed but outmoded function of Other.

So how does this impact performance? One of the primary performance modifiers is distraction. Distraction, like nearly all of the performance modifiers, can have a positive or a negative impact on performance. A distraction as significant as a loved one dying immediately prior to a performance can provide a distraction strong enough that the performance becomes automatic and can result in a lifetime best performance. A distraction as insignificant as seeing a rival standing close to your life partner can overcome several years of training and undo a performance in a matter of minutes.

Being triggered to unconsciously react to a constant barrage of Other related events pulls energy and focus away from the task at hand. Normally this is not an impairment to performance, we have enough slack to accommodate the distractions. When the performance requires the majority of neurological and physical resources the distraction becomes a significant impairment factor.

Distraction isn’t the only challenge that is driven by the Other. Chronic over stimulation of Otherness can lead to a number of physical manifestations including: hypertension, immune disorders, ulcers, depression, phobic behaviour and pathological rage, just to name a few. None of these conditions are known to enhance performance and most are seen to degrade performance.

Crap, what can be done about this?

Awareness is the prime antidote to the condition. Along with becoming aware of when mood, attitude or motivation changes without a discernable change in environment we can alter the way in which we process our Other based perceptions. It is widely known that the same stimulus has markedly different impacts depending on how the stimulus is perceived. An individual who has developed perceptions that interpret Other as an opportunity for growth and development is more likely to gain from the experience than an individual who perceived Other as a threat or burden.

To enhance awareness of Other based perceptions that have a significant negative impact, exercises like perspective taking can have a positive impact. The first step in the perspective taking process is to identify an area where Other based perceptions provide enough distraction to impair performance. Once this is accomplished it is a simple matter to take the perspective of the Other to see the situation through their ‘eyes’. The word eyes is in parentheses because the Other may not be human and may not even be living. The act of taking the perspective of the Other often works to lessen to the negative power of the Other when we realise that the intention that we attributed to the Other may not be what we perceived or may not even be intentional at all.

The power of the Other is significantly enhanced by an extreme focus on difference. Making a conscious effort to seek out similarity can have an impact on lessening a perceived threat and significantly reduce the power and impact of the Other on us. As soon as we have something in common with the Other, the Other loses some of its Otherness.

Another benefit of gaining awareness of strong Other perceptions is that the concept of Priming can be used to minimise the impact of the Other. Priming is an odd feature of our neural processes where some completely unconnected idea can get associated with another idea and impact the resulting behaviour. The classic Priming example takes place in the showroom of most companies that sell high value products. If the marketing folks are tuned in to the effect of Priming, the very first thing that you will see as you enter the showroom are the most expensive products that they have, with the price clearly visible. There is little to no intention to sell you the expensive product, the Prime is in the price. Seeing the high number, you are now primed to perceive the price of the lower priced products as better value than you would have if you had not seen the large price number. How can we use this to our advantage? If we know that we are likely to encounter an Other that will negatively impact our performance we can Prime ourselves by associating the Other with positive experience that enhances performance.

And the circle is complete

We are complex beings, non-linear by nature and prone to behaviours that we are not even aware of. In the area of the Other we can come closer to the goal of ‘know thyself’ by improving our awareness of this formerly undocumented feature. To know that the Other is primarily a construct of the self is to know the self.

The discovery of just how this aspect of our neural makeup works is actively being pursued by some of the most disciplined minds ever generated. Take a bit of your time to keep up with what is being discovered in this area. Your performance will improve as fast as your mind can incorporate these new ideas.

What Don did was look at the performance of successful people in any field and interview them extensively. This gave Don a mountain of data. He then sifted through the data and came up with a collection of talent areas that he called Strengths. He identified 34 talent areas or Strengths. He sorted these into 4 performance sectors or Domains. He now had an outcome tool. From his interviews he captured the perspectives that identified each of the strengths and from those perspectives he created an assessment tool that he called the StrengthsFinder (now known as CliftonStrengths®).

What Don did was look at the performance of successful people in any field and interview them extensively. This gave Don a mountain of data. He then sifted through the data and came up with a collection of talent areas that he called Strengths. He identified 34 talent areas or Strengths. He sorted these into 4 performance sectors or Domains. He now had an outcome tool. From his interviews he captured the perspectives that identified each of the strengths and from those perspectives he created an assessment tool that he called the StrengthsFinder (now known as CliftonStrengths®).

The process is simple:

The process is simple:

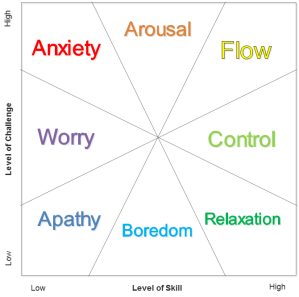

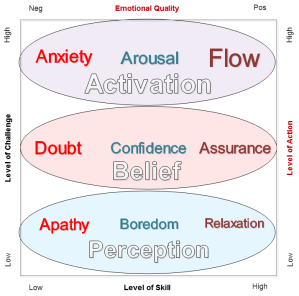

The model is a simple matrix using two axes, one for a progression of intensity (Level of Challenge) and one for a progression of capability (Level of Skill). Eight emotional states populate the interior of the matrix representing the path to the Flow State.

The model is a simple matrix using two axes, one for a progression of intensity (Level of Challenge) and one for a progression of capability (Level of Skill). Eight emotional states populate the interior of the matrix representing the path to the Flow State. With the revised model it is now possible to see that where it is possible to generate high Quality Emotions in situations that require high Skill and offer a high degree of Challenge combined with high levels of Action a Flow State will have an increased likelihood of occurring.

With the revised model it is now possible to see that where it is possible to generate high Quality Emotions in situations that require high Skill and offer a high degree of Challenge combined with high levels of Action a Flow State will have an increased likelihood of occurring. With the realisation that the second level of the matrix deals with Confidence, terms more appropriate for expression of Confidence can now be used. Worry is replaced with Doubt and Control is replaced with Assurance.

With the realisation that the second level of the matrix deals with Confidence, terms more appropriate for expression of Confidence can now be used. Worry is replaced with Doubt and Control is replaced with Assurance. The mystery of Flow State achievement now begins to be unravelled. We see that development in the areas of Perception, Belief and Activation will lead to an improved likelihood of consistent Flow State achievement. It is highly possible to work effectively in each of the three continuums. Each of the three continuums can be worked on independently. Creating a program to address and improve function in the three continuums will improve general performance maturity which, in itself, will improve performance while making Flow States easier to achieve and more frequent in their occurrence.

The mystery of Flow State achievement now begins to be unravelled. We see that development in the areas of Perception, Belief and Activation will lead to an improved likelihood of consistent Flow State achievement. It is highly possible to work effectively in each of the three continuums. Each of the three continuums can be worked on independently. Creating a program to address and improve function in the three continuums will improve general performance maturity which, in itself, will improve performance while making Flow States easier to achieve and more frequent in their occurrence. As the model now indicates the path from Novice to Master is also the path to being able to consistently establish a Flow State during performance. It is quite likely and totally consistent with the model to have a performer operating at each of the three maturity levels simultaneously. In fact, this would be considered to be the norm. A performer may have certain elements of the performance that are fully mastered where Flow State occurs consistently and naturally. The same performer will have areas where only the Performer level has been attained and Flow State is only rarely attained during those aspects of the performance. And, of course, the same performer can have areas where the Novice level exists. These areas would most likely be areas where very new technique or capability is being introduced.

As the model now indicates the path from Novice to Master is also the path to being able to consistently establish a Flow State during performance. It is quite likely and totally consistent with the model to have a performer operating at each of the three maturity levels simultaneously. In fact, this would be considered to be the norm. A performer may have certain elements of the performance that are fully mastered where Flow State occurs consistently and naturally. The same performer will have areas where only the Performer level has been attained and Flow State is only rarely attained during those aspects of the performance. And, of course, the same performer can have areas where the Novice level exists. These areas would most likely be areas where very new technique or capability is being introduced.